Before I begin the actual content of this research article, I would like to address a few things. Firstly, to the Professor reading this, the medium I've chosen for this project is this blog, which I use to talk about my ideas for stories and media analyses. Also, to briefly defend how this topic fits within the rubric of "a particular topic...in astronomy", I believe that one of the foremost interests of most people when it comes to astronomy is how humanity will expand beyond Earth; I also believe that Dune is one of the most well-thought-out depictions of what that future may look like, hence how I ended up on this subject.

To any readers of my prior posts now reading this one, I would like to say that I still intend on turning this analysis into a video, however I just couldn't see myself doing so in a sufficient way by my assignment deadline. It may evolve into a somewhat different topic, but I do plan on completing it. I'll be working more on that over the coming weeks, potentially months. But until then:

The Good Imperialist

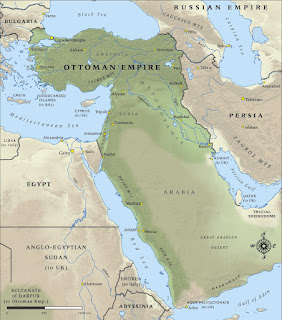

By the point in time where the novel begins, there are three main Imperial forces exerting influence over Arrakis: the feud between Houses Harkonnen and Atreides, the Bene Gesserit, and the Planetologists. Of these three, the first is the most one-to-one example of imperialism, drawing heavy parallels to the Arab Revolt in the Hejaz (pp. 189-221) against the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

|

| Source: NZ History |

The world of Dune, although not an exact recreation, is quite similar; the Harkonnens have ruled the Fremen for decades with a bloody, oppressive fist. After eighty years, the Harkonnens are made to withdraw from Arrakis, and the Atreides family assumes control over the planet. Sensing imminent retaliation from the Harkonnens, Duke Leto seeks to convince the Fremen to fight with him against their former oppressors, promising better lordship in return.

While Leto's plans ended up failing, leading to the fall of his House and his own demise, the British were ultimately successful in using the Arab Revolt to weaken the Ottoman Empire. However, unbeknownst to the Arab people, the British and French governments had formed the Sykes-Picot Agreement, dividing up the Middle East into spheres of British and French rule, betraying their promise of full Arabian sovereignty. While this would not be the final agreement in divvying up the region, it was certainly the most influential.

|

| Source: Britannica |

At this point, you may be wondering how this correlates to Dune and what its worldbuilding seeks to convey; Duke Leto was honorable, and should he have won against the Harkonnens he might have fulfilled his promises to the Fremen.

But while this may be the case, is there really such thing as a "good" imperialist? House Atreides is ultimately an extension of the Imperium's rule, a government the Fremen people have had virtually no desire to be a part of. The only one who benefits from Arrakis' imperial occupation is the Imperium, siphoning away the planet's spice and giving virtually nothing in return.

There is no such thing as a good imperialist. At its best, House Atreides would rob the Fremen of their resources and sovereignty, all after coercing them into a blood feud that barely involves them.

Abandoning the route of the hypothetical, we enter the reality of the novel, wherein Duke Leto is killed and Paul flees to the desert, becoming a living messiah to the Fremen. Looking back to the Sykes-Picot Agreement, we see how Britain's use of the Arab people in their war led to the theft of land. But it is through Paul's ascension as Muad'dib that we begin to understand how imperialism not only robs peoples of their resources and sovereignty, but also of their faith.

Religion and Politics

But Paul's place in history was precipitated hundreds of years ago by another faction; the Bene Gesserit.

|

| Source: Polygon |

There's a lot to say about this myth itself, and how through it Herbert criticizes the white savior narrative, however that is another subject for another writer. For now, I believe there's much to be learned from the way the Bene Gesserit influence and control the Dune universe, and its reflection of the way our own politicians do so.

In a 1969 interview with Frank Herbert (30:15), Herbert discusses "the Voice", a power the Bene Gesserit use to forcibly control other persons. What's particularly interesting about his discussion is his claim that the Voice is used all the time in politics; through understanding a person, he claims you can goad them into anger simply through your voice. In a similar sense, politicians understand their constituents, and thereby prod them to illicit a specific outcome.

It's very different to the instant, visceral obeisance of those the Bene Gesserit use the Voice on, however I find it to be a very interesting comparison. To go further with this metaphor, Paul and Lady Jessica's willful manipulation of the Lisan al-Gaib mythos in order to ensure their survival on Arrakis is also reminiscent of the political game; just as Paul instills himself as the religious head of the Fremen to maintain control, so too did rulers such as Henry VIII consolidate power by asserting control over their subjects' religion.

|

| Source: CNN |

found as a rallying cry behind the recent calls for an abortion ban, as American politicians use Christianity to limit a woman's autonomy. The main difference between the Bene Gesserit and a politician is that, through narration, we understand the intentionality of each choice--the active manipulation of religion for the Atreides' benefit, the, albeit sparing, use of the Voice to impose a Bene Gesserit member's will upon their target, and the pulling of strings in the background to manipulate the Imperium.

Dune does not outright tell us that our leaders use religion or charisma to manipulate us; it instead shows us what this might look like, and encourages us to look for it in the real world.

The Western Man and Cultural Assimilation

The final force of the Imperium imposing itself upon the Fremen people are the Imperial Planetologists, Pardot and Liet Kynes. Out of the three, the Planetologists are the most interesting case; they, representatives of the Imperium, seek to change Arrakis--to turn the dunes into waves.

The project began with Pardot, an Imperium-born man, as he gave the Fremen the dream of terraforming Arrakis, and was later passed down to his son (in the movie adaptation, daughter) Liet; half-Fremen, half-Imperial. Pardot taught Liet everything he knew about planetology, and it is through Liet that we see the beginnings of acculturation, and what this off-worlder's dream will truly mean for the Fremen.

|

| Source: The Hollywood Reporter |

1969 interview (10:05), Herbert points out the irony of the scene, of how Kynes, in his final moments, observes the ecological process of the spice eruption forming beneath him, an eruption that will result in his demise. It becomes an odd moment wherein Kynes is able to understand all these mechanical processes, yet cannot see that he is only one cog in the massive machine of Arrakis, that despite his infliction of himself and his father's dreams upon the planet, he is still just one man, who may live and die by the whim of Arrakis. As Herbert mentions in the interview, and later writes in Dune: Messiah, "One tended to believe power could overcome any barrier...including one's own ignorance" (p. 183).

This way of thinking goes deeply against Fremen culture. They live in harmony with the desert, fashioning tools and technologies to adapt. Where the Harkonnens had to frequently stop mining spice, as their harvesters would attract sandworms, the Fremen developed Thumpers to distract the worms, and learn to sandwalk so as to become sonically one with the desert. This juxtaposition between the Harkonnen's, ultimately the Imperium's, and Fremen's relationship with the planet can be found in Liet Kynes, raised in Fremen culture but taught the Imperial mindset, ultimately resulting in his living in disjunction with the way of Arrakis.

It is a microcosm of what the future may hold for the Fremen, following this dream given to them by the off-world planetologists. Yes, the desert is brutal, and having water on Arrakis is a dream unfathomable to most Fremen; but to take away the desert would be their demise. To bring water to the desert is to eradicate the foundation of the Fremen culture.

In Defense of the Soft Sciences in Science Fiction

Science fiction pushes the limitations of our reality. Interstellar dedicated itself to scientific accuracy in all facets of its story, and in doing so created the most scientifically accurate model of a black hole in human history. Countless works pushed forth humanity's dream to travel by way of land, air, and sea. It is through these reimaginations of the natural sciences that we achieve creative innovation, and the drive to improve our world.

And yet Dune gives us insight on the world as it exists before us. It illuminates the soft sciences: anthropology, theology, political science--the foundations of human society and culture. It reveals to us that for as much as science fiction teaches us to dream, it must also cause us to stop for a moment and think--to understand the world for what it is, so we can shape it into what it could be.

References

Bali, A. (2016). Sykes-Picot and "artificial" states. Cambridge University Press.

Anderson, A., Khalidi, R., Muslih, M., & Simon, R. S. (1991). The origins of arab nationalism. Columbia University Press.

mengutimur. (2017, May 6). Frank Herbert on the origins of Dune (1965) [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A-mLVVJkH7I

No comments:

Post a Comment